Playing the Game to Change the Rules: Thinking and Working Politically to Advance Inclusion

This is the third of four posts reflecting on the linkages between gender awareness and politically sensitive approaches to programming known as Thinking and Working Politically (TWP). I will be posting one additional blog next week.

The first blog in this series addressed my personal epiphany regarding the potential for thinking and working politically to narrow our focus in a way that limits the space for critical considerations around gender and inclusion--and reflects on new resources to help us do this better. The second blog addressed the integral nature of gender and inclusion to any effort to think and work politically.

The final blog, to be posted shortly, will reflect on recent experience within USAID, and consider the path forward, including tools to support an effective merger of considerations around gender and inclusion.

Please note that while the principles discussed can be applied to all aspects of inclusion, the current resources are focused on gender, as a key dimension. As further learning becomes available, we’ll look to share more.

Click here for other blog posts in this series.

At the turn of the 20th century, little in the American women’s suffrage movement inspired optimism. Leadership of the new National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) had rested for a decade with two elderly “radicals,” Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Stanton courted controversy and took pride in a “special mission” to “tell people what they [were] not prepared to hear.” 1 In this atmosphere of confrontation, progress toward women’s voting rights seemed stalled.

After 1900 the strategy shifted. While Stanton had demanded suffrage on the basis of strict equality, the NAWSA now argued for women to have the vote, not because they were equal to men, but because they were better. Framed by the image of women as mothers, pious and pure, women’s suffrage was promoted as a path toward more moral governance, guiding the movement into the mainstream.

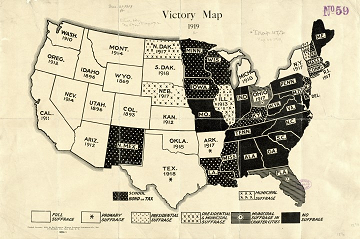

Carrie Chapman Catt, self-identified as an “Iowa farmer’s daughter,” embodied this approach. She assumed leadership of the NAWSA for the second time in 1915, and launched a new “winning strategy.” Statewide campaigns would press for suffrage in at least 36 states. Women voters would pressure their elected leaders to pass a Constitutional amendment. States where full suffrage had already passed would focus on the national campaign. In states where full suffrage was not politically viable, partial suffrage would be pursued.2

When the U.S. entered World War I, the NAWSA embraced the war effort within its mission, thereby attracting a new and influential member to its supporting coalition - President Woodrow Wilson. Previously noncommittal on the question of suffrage, Wilson went before Congress in 1918 to argue for full suffrage as a vital part of the war effort. “We have made partners of the women in this war,” he reflected, asking “Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?”3

None of these strategies achieved immediate or independent success--not even the support of the President. Together, they ultimately yielded dramatic change: In 1919, the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution passed; when ratified in 1920, American women were guaranteed the vote.

I thought of the suffragists while reading work from the Development Leadership Program (DLP) which discussed application of principles of Thinking and Working Politically (TWP) to advance inclusion - or “playing the game to change the rules.”

Carrie Chapman Catt - sometimes called “the general” - didn’t require our instruction to think and work politically. Yet, the approach is not automatic. As donors supporting inclusion goals, we face our own hurdles, including the potential for our assistance to distort a movement and impact its sustainability. I’m left wondering: when promoting inclusion, is working politically really separable from working with gender awareness? Are there tensions between the two?

Lacking an easy answer, I turn to the cases and am struck by the stories of two programs where donors sought to promote locally grounded inclusion.

WE CAN, a 2004-2011 campaign supported by the UK and Dutch Governments and Oxfam is a case of playing the game to change the rules. The campaign involved hundreds of organizations in 16 countries seeking “to challenge and change entrenched attitudes that support and justify violence against women [VAW] at the individual, community, and society levels.” Employing a “change maker” approach, participants were encouraged to reflect on their own practices, end VAW in their lives, and talk to 10 others about it. The campaign targeted men, suspending judgement to enable men who acknowledged past violence to become part of the solution. By 2011, the program had signed up around 3.9 million change makers, with 7.4 million people participating in related activities. Half of all change makers were men, a crucial factor in the campaign’s success.

Through the change maker approach, the campaign broke down a large and sensitive problem and made it accessible—finding spaces where participants saw possibilities to actually do something. The specifics varied according to the context; hence, the strategy’s success partly depended on decentralized approaches to implementation.

Notwithstanding their success, concerns were sometimes raised in the course of strategies targeting men. Some saw the messaging as reinforcing the role of men and boys as protectors of women. Seen in this light, through its efforts to encourage the participation of men, the campaign failed to challenge - and may even have reinforced - underlying power imbalances.4

Another case comes from Indonesia, where women confront challenges with persistent inequality, reinforced by laws and social norms. The Australia-Indonesia Partnership for Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment (MAMPU) works to support the collective capacity of women to influence policy and resource allocations. Partner organizations, selected based on their capacity to promote change, are supported to build networks, a shared vision, and collaborative approaches to women’s empowerment. Building connections with reform-minded leaders at all levels of government is a major part of the strategy. A review of the program indicates that MAMPU partners are increasingly positioned to influence key policies nationally, along with growing village-level networks, membership in local groups, and engagement on local priority issues.

Reflecting on these and other cases, I find myself questioning the assumptions that we make about TWP. The literature contrasts gender analysis - with its attention to individual and household dynamics - to TWP described as focused on higher level, more formal dynamics. Citing this as a tension, it calls for extending the definition of TWP to encompass individual, household, and community-level dynamics. I always assumed such dynamics to be woven throughout TWP. I’ve explored them in my own PEA experience, as well as within our recently updated PEA guidance. As the TWP community grows, clarifying these understandings becomes more important.

Other lessons are more straightforward. Supporting local actors as they develop the strategy can help to manage the risks these stakeholders confront, develop local leadership capacity, and ensure that any compromises are locally owned. And while many associate TWP with a focus on broadly impactful policy reforms, the intermediate objectives and measurements of politically informed programs can be very modest. The increased membership of a community organization - even a single man’s change of heart - can be transformational in the long term.

And so Susan B. Anthony reflected to Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1902, writing just before the latter’s death, “We little dreamed when we began this contest...that half a century later we would be compelled to leave the finish of the battle to another generation of women. But...they enter upon this task equipped with a college education, with business experience, with the fully admitted right to speak in public - all of which were denied to women fifty years ago. They have practically one point to gain - the suffrage; we had all.”5

_____________________________

1 Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. Eighty Years & More: Reminiscences 1815–1897. Northeastern University Press; Boston, 1993, p. 372.

2 See https://brilliantmaps.com/1919-womens-suffrage-victory/.

3 See full text of speech: http://www.public.iastate.edu/~aslagell/SpCm416/Woodrow_Wilson_suff.html.

4 See http://publications.dlprog.org/CS8.pdf.

5See https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2014/julyaugust/feature/old-friends-elizabeth-cady-stanton-and-susan-b-anthony-made-histo