Thinking and Working Politically... and Inclusively

This is the first of four posts reflecting on the linkages between gender awareness and politically sensitive approaches to programming known as Thinking and Working Politically (TWP). In the coming weeks, I will be posting three additional blogs.

The next will discuss the integral nature of gender and other inclusion analysis as a part of TWP. After that, I’ll explore how gender analysis and political analysis can be merged to promote inclusion--including where, if at all, the two lenses conflict. The final blog will reflect on recent experience within USAID, and consider the path forward, including tools to an effective merger considerations around gender and inclusion.

Please note that while the principles discussed can be applied to all aspects of inclusion, the current resources are focused on gender, as a key dimension. As further learning becomes available, we’ll look to share more.

For other blog posts in this series see: https://usaidlearninglab.org/resources/blog-series-thinking-and-working-politically-and-inclusively

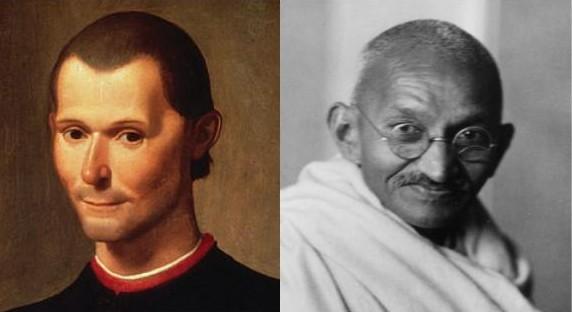

“How we live is so different from how we ought to live that he who studies what ought to be done rather than what is done will learn the way to his downfall rather than to his preservation.” - Niccolò Machiavelli

“All the tendencies present in the outer world are to be found in the world of our body. If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change.” -Mohandas Gandhi

Sometimes, when I close my eyes, I envision our work as a mythical tug of war. On one side is an ideal—the image of the world as it ought to be, and of myself and my colleagues as we should be living and working; on the other—the inexorable pull of pragmatism.

This tension has become such a fixture in my life as a development professional working within a bureaucracy that I often forget it exists. I was reminded of it a couple of years ago in the midst of debating the focus of a case study for our Political Economy Analysis (PEA) workshop. We had settled on an old favorite - the story of land reform in the Philippines, implemented by the Asia Foundation under a cooperative agreement with USAID. The story offered actual results and a compelling video that captured its success.

And then, one colleague broke the consensus to ask - “Where are the women?”

It was a fair point. The video tells the story of three Filipino men who engaged in work that positively impacted the lives of thousands of Filipino men and women. Yet, the women in the video were silent. Women on the team listened attentively around a conference table and typed with attractively manicured fingers. Other women smiled wordlessly as they held up their new land titles, while men described the difference those titles made to their lives. Beyond these optics, the story focused on the importance of male-dominated university networks and social spaces to finding workable solutions, emphasizing those points with images of cigarette smoke and beer.

The realization was unsettling. I recalled PEA interviews where men spoke past me to connect with another man - and the times I declined the lead on an interview because the stakeholder would relate better to a man. Such decisions made sense as we pursued the best information around thorny development issues...but they also made me feel just a little bit smaller.

We decided to use the video - and the Philippines case study - for all the reasons that we liked it in the first place. But we also concluded that this was a tension to lean into. We initiated conversations within our trainings, sometimes awkwardly, acknowledging that we had more questions than answers about the balance between political feasibility and the value of inclusion.

We are fortunate that others have also been thinking about these knotty issues. The Development Leadership Program (DLP) at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom recently produced a number of resources looking at how political sensitivity and gender awareness can be merged in programming. It takes into consideration the literature and digs into a number of programs that sought an effective balance between attention to gender dynamics, the value of inclusion, and pragmatic, politically aware approaches.

The work argues that “politically informed” and “gender aware” efforts have operated on tracks that rarely intersect, hindering our accurate understandings of the context. The case studies highlight two manifestations of the intersection of gender and Thinking and Working Politically (TWP): gender as a key dimension of power to be understood, regardless of objective; and the application of TWP principles into programs aimed at inclusion. In the stories, I also see some synthesis of the two: cases where actors work politically toward any goal with attention to the impacts (positive or negative) on gender and inclusion.

The DLP resources will illustrate the possible tensions when balancing political sensitivity with gender awareness, and paint a picture of what it looks like when the lenses are effectively merged. Yet, they left me wanting greater practical guidance on pursuing this balance. For this, I was excited to see the guidance note from the Gender and Development Network (GADN), on gendered PEA. Addressing the need for such a tool, the note says “political economy analysis is often so focused on understanding how things are that it misses seeing what and who are absent from power and politics, and fails to imagine how things could be.” This resource is one that I think can help us overcome such failures in imagination.

I’ve been reflecting on these resources, which I’ll share in future blogs while I struggle to respond to the fundamental question: How can we, like Machiavelli, recognize the world as it is, while we also channel a bit of Gandhi, and remember just how much we are a part of that world?

Perhaps, some of this thinking and resources, may help us achieve this balance, and avoid conflating realism with complacency. Change too, is inevitable, and we may well be surprised by the direction or magnitude of that change. And, even as a minor actor in the system, who we are and how we work may help steer those changes in one direction or another.