Towards a More Thoughtful Approach to Decision-Making

Effective decision-making - how it’s done and what decisions come to be - is a critical component of effective management. And it’s essential for adaptive management - you can’t be intentional about adapting if you don’t take time to think about what you’ve learned, make decisions based on that, and then take action (see more on this here). In creating the guide to hiring adaptive employees, I came across a variety of sources that highlighted the importance of decision-making and the concept of decision quality. In the guide, it became one of the key competencies of an adaptive employee. It is the ability to make quality decisions based on a mixture of analysis, evidence, and experience.

And if I’m being honest, I am in a management role and oftentimes feel myself being a little unsure about my decisions. I realized I needed a personal checklist or approach to help me become more thoughtful in my decision-making in the hopes that this would make me a more effective leader and adaptive manager. Here’s what I’ve been thinking about:

Before even making a decision, I realized I need to ask myself at least four key questions:

- Is there urgency? I tend to move quickly, and that’s not always a good thing. First consider: is there real urgency? When does the decision need to be taken in order to avoid delays or the loss of momentum? If you have the luxury of some time, then take advantage of it, even if it is just a couple of days. At the same time, if there isn’t clear urgency, but something is still a priority, do not let decisions languish. You will lose momentum and motivation, and more time is not correlated with better decisions. Ultimately, considering this question informs what your decision deadline should be. Work back from that to know how much time you have to gather more information and think through alternatives.

- How risky is this? Riskier decisions need to be considered more carefully. And risk is multi-faceted - consider not just financial risk but also risk to important relationships, to achieving our objectives, to our reputation, etc. (USAID’s risk appetite statement has a great list of various types of risk.). Part of CLA is figuring out ways to test new approaches while minimizing risk. But before making a decision, figure out what’s at stake. Is it really serious, or is it the case that regardless of the decision you take, the repercussions would be minimal? If the latter, move faster. (See this great framework from Adam Grant on decision-making and risk.)

- Should I even be making this decision? Sometimes a staff person comes to you with a decision that needs to be made, but is it really yours to make? Sometimes it is, but we can easily forget that it’s important to give staff autonomy to make decisions about their work. Enabling decisions to be made as close to the work as possible can increase autonomy and overall employee satisfaction with their job. Don’t forget to push back if your staff should really be deciding. Instead of deciding for them, you can coach them through the decision by asking good questions: What are the advantages and disadvantages of going one way or another? Can you think of any alternatives to the options you’ve already established? Who has experience with this situation that you could learn from? (See below for some considerations for potential coaching questions.) On the other hand, if you determine that the decision does rest with you as the leader, then own that, don’t punt, and communicate how the decision will be made to manage expectations.

- Who else should be involved in making this decision and how should we decide? Let’s say you should be involved in making this decision - are there others who need to be involved as well? Think about people deeply affected by the decision or who need to act on the decision. What kind of decision-making approach is appropriate for the level of urgency and risk? In development, we tend to default to a consensus-based model. I’m generally not a proponent of this approach. Sometimes it makes sense because you really do need everyone bought in. But it can be time-consuming, cause delays, frustrate those on different sides of an issue, and result in all kinds of compromises so the decision is diluted or meaningless. One of the first questions I ask USAID clients is “how are you going to decide this?” Is it a consensus model? Is it staff providing alternatives that leadership decides on? Is it a majority vote? All of these models could make sense depending on the situation, but you need to be intentional and transparent about what process you will use.

Now, you’ve determined that you are the person that needs to make the decision and that you at least have a couple of days to do so. Let’s say there’s medium risk. Here are some other considerations to help you get to a quality decision:

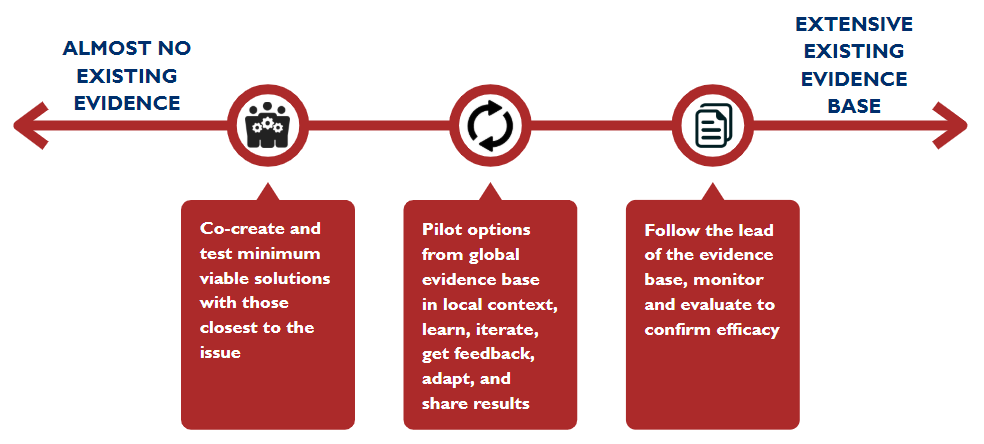

- Is there an evidence base that can inform this decision? Evidence base refers to existing literature (grey included), data, analyses, assessments, evaluations, and even reflections on prior experience. Are you familiar with the evidence base? Do you know someone who is and can point you to useful resources? Sometimes you are charting new territory and there is very little evidence to help guide you or the evidence that exists is mixed and inconclusive. When you find yourself in this situation, make sure you plan to share out your experience so that others can benefit from the evidence you’ve generated the next time they face a similar decision. See the graphic below for options depending on the status of the evidence base.

- What do I know based on my personal experience? Has a similar situation happened before? How did you handle it? Which factors were the same or different? What were the outcomes? Ultimately, what can you apply from your previous experience to this decision? Access your personal wisdom.

- What can I learn from others’ experiences? If you haven’t faced a similar situation or experience, what can you learn from others that have? A common tool that we use on LEARN is a before action review - this is a simple approach to ask others who have tried something similar about what happened, what worked, what didn’t, and what they would do differently next time to inform your decision.

- Are there alternative options that need to be considered? There are rarely only two options. Consider what else could be possible before making a decision. To get your creativity flowing, ask yourself questions like: if there were no restrictions, what would I do? Or if I had a magic wand, what would I do? If money and resources were not an obstacle, what would I do? Or, if it’s a year from now and things worked out, what decision(s) led to that point? Sometimes this opening can get you to new ideas and options, even if your authority or resources are limited. Consider this and other decision-making insights from the Heath Brothers.

You’ve considered these questions and you’ve made a decision. Now what?

- Document your decisions and the rationales. There is a phenomenon called hindsight bias which refers to how we make sense of decisions after the fact. It’s important to remember why you decided something and, per the below bullet on reflection, refer back to those documented reasons so you don’t succumb to hindsight bias yourself.

- Share the design and rationale with those affected. If they weren’t involved directly in making the decision, those affected by it deserve to know what was decided and why. For management reasons, perhaps not everything can be shared, but share enough so you are communicating your leadership values along with the decision.

- Reflect on the decision-making process and your rationale. After there’s been time to see the results of the decision, evaluate your own decision quality. I would spend less time on whether it was a good or bad decision (again, because of hindsight bias, we can often rationalize prior decisions, so it’s not a great use of time). Instead, reflect on the process and the justifications you used for the decision. Was the process a good one? Were the justifications you used accurate and in line with your personal and organization’s values?

I hope these considerations are helpful to you in your decision-making journeys. Leave us feedback on how you approach decision-making, what you like, or what I maye hvae gotten wrong!