The Tradeoffs of External Versus Internal Developmental Evaluation

The Tradeoffs of External Versus Internal Developmental Evaluation

With developmental evaluation (DE) now recognized in USAID’s Operational Policy for the Program Cycle, Missions, Washington-based Operating Units, and implementing partners (IP) are putting it into practice but often with key differences.[1] Foremost is whether the developmental evaluator is internal or external to the IP conducting the program being evaluated. While both are legitimate approaches, they have unique tradeoffs in terms of credibility, contract administration, and collaborating, learning, and adapting (CLA) that funders and implementers should consider.

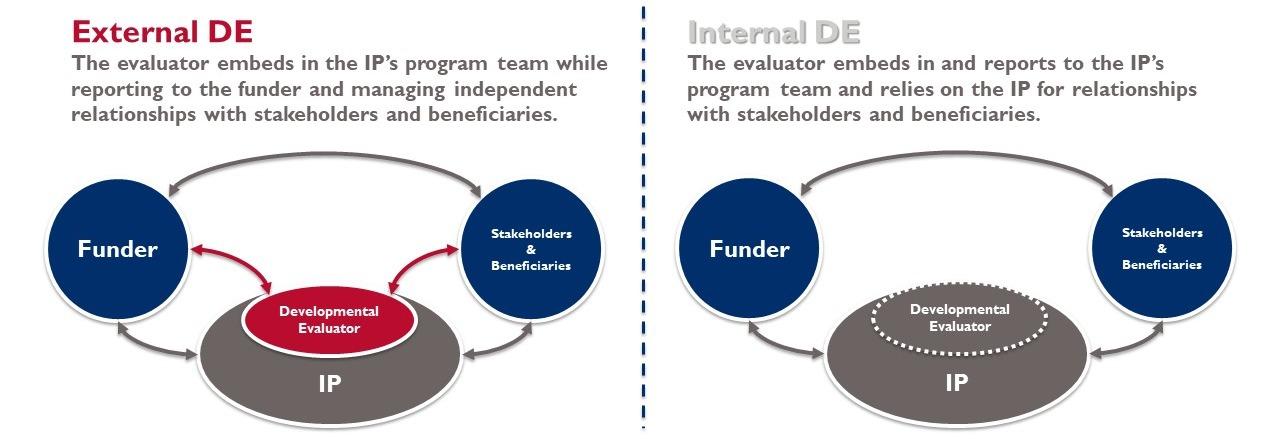

Embedding in External and Internal DE

An external DE is conducted by one or more evaluators contracted by and reporting to the funder, while an internal DE is when an IP deploys developmental evaluators who report to them to assess their own program.[2] The concept of “embedding” – a key tenant of DE (see Figure 1) – complicates this decision.

Figure 1: Embedding the Evaluator in External and Internal DE

Embedding evaluators enables them to operationalize CLA and support adaptive management by informing donor, IP, and stakeholder decisions with real-time feedback collected via their unique position inside the program. To be successful, the donor and stakeholders must value the DE’s advice as objective, while the IP must consider the DE a trustworthy and valuable member of its team.

Tradeoffs

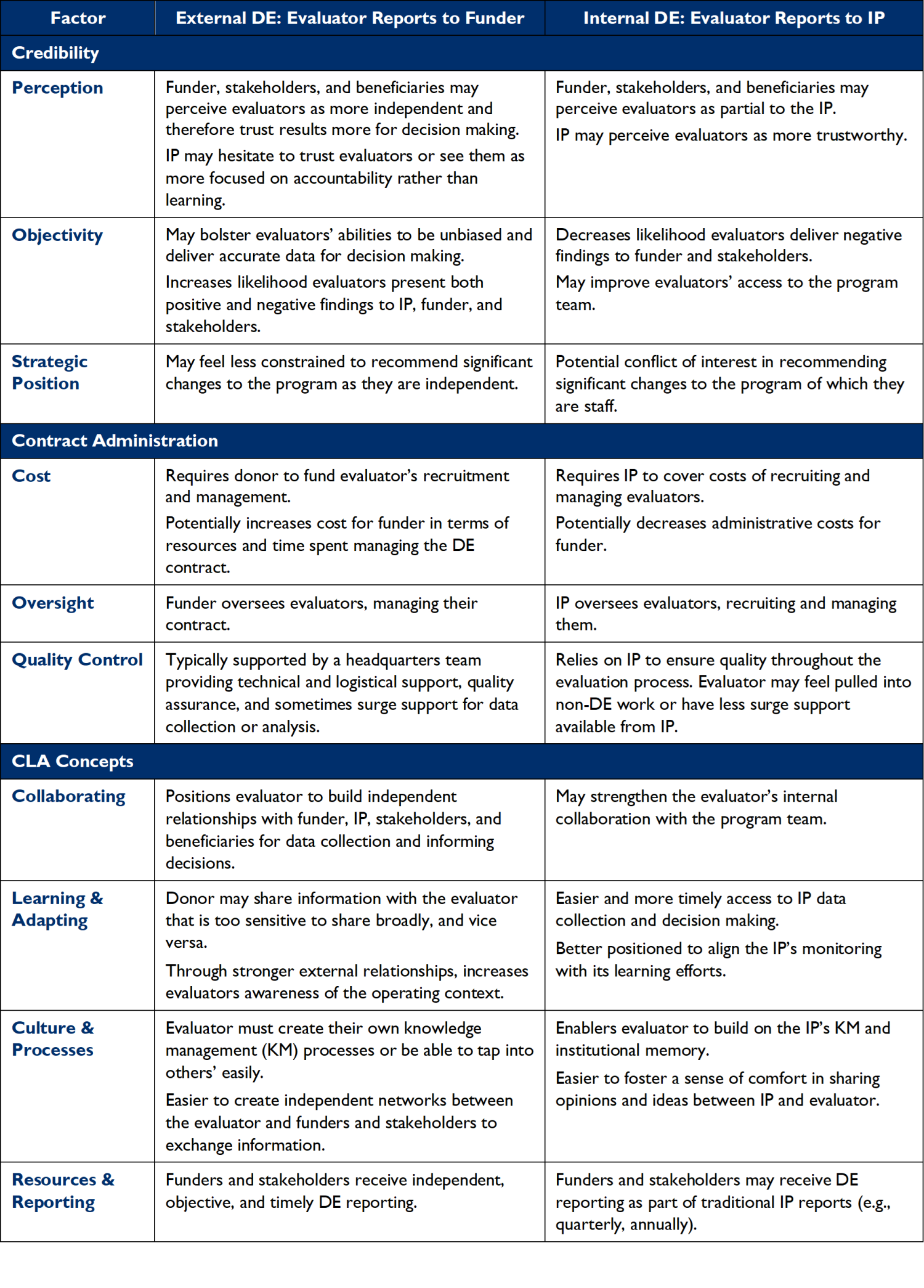

The balance evaluators need to strike to successfully embed means funders and implementers should carefully consider the tradeoffs of external and internal DE when deciding between them (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Tradeoffs between External and Internal DE

External DEs typically exhibit more collaborative relationships with funders and stakeholders due to their perceived independence and objectivity while exhibiting larger teams with support staff. They are more likely to share negative findings and engage Missions in frank discussions about potential changes in strategic direction. Internal DEs usually enjoy easier access to program data and have smaller teams because they report to the IP which supports them. They are more likely to focus on small scale programmatic adaptations rather than strategic changes.

While the table above considers administrative cost, studies have not determined a significant difference in overall funding between external and internal DE because DE budgets vary significantly.

Furthermore, funders and implementers can mitigate these tradeoffs. For example, IPs can adapt their organizational structures to strengthen an internal DE’s independence, and evaluators can deliver quick wins to strengthen their perception as being trustworthy and valuable to the program in external DE.

Deciding Between External and Internal DE

Deciding between external or internal DE should be governed by what approach is most useful to those involved. Credibility, contract administration, or CLA considerations may drive this decision, but these tradeoffs do not affect the essential role of DE. Because DE is a mindset of inquiry rather than a set of methods, it can take either form. Whether external or internal, the embedded evaluator should aim to bring evaluative thinking to a program team engaged in innovation and support their decision making and adaptive management with real-time data and feedback.

[1] For background on the DE approach in general, please see the resources available on USAID’s Developmental Evaluation Pilot Activity (DEPA-MERL) website: https://www.usaid.gov/PPL/MERLIN/DEPA-MERL

[2] USAID’s DEPA-MERL website features a case study series which includes external and internal DEs.