Eat More Broccoli: Moving from Talking to Doing Adaptation in Delivery

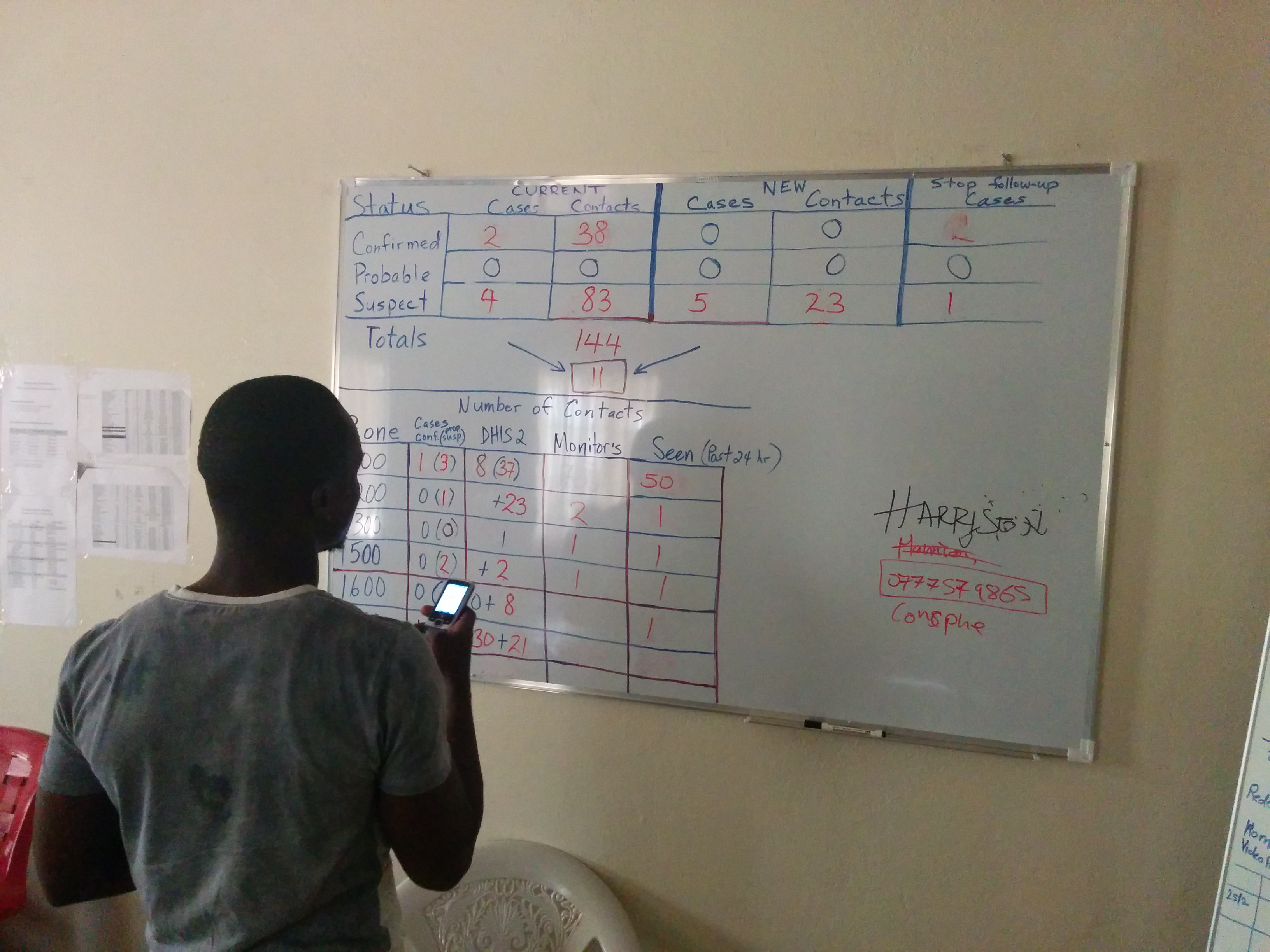

Image: Vargo Degbe, from the Monrovia Ebola task force, tallies the day's case data

Just what the development community needs: another piece arguing for working in more problem-driven, politically smart, adaptive ways. Isn’t that like your doctor telling you to eat more broccoli? We’ve heard it before and we agree in principle, but that doesn’t make it actually happen.

That’s been my lingering concern as we launch the third article in the Africa Governance Initiative’s Art of delivery series. In Changing it up, I make the case that delivery mechanisms – systems that seek to improve implementation of leaders’ priorities – are only effective when they’re customized to the context.

So why is this discussion important?

First, because though many in development are talking about the importance of working in context specific, adaptive ways, the delivery crowd has been slow to join the party. One possible reason for this is that delivery isn’t just a development trend; delivery approaches are popping up in places like Canada and Maryland as much as in developing countries. We’d like this paper to help bridge the gap between these development and delivery discussions.

Second, even if you believe testing and adapting is the way to get a delivery system to work, embracing this in practice is hard and uncomfortable. For donor-funded delivery initiatives, if implementing organizations commit to setting up a delivery team with specific structures and procedures, making changes risks looking like failure. It’s tempting for everyone to just stick to the original plan. But that won’t get to an effective delivery system. Funders and implementers need to work together to break away from these habits or else delivery is doomed to repeat development’s form over function mistakes of the past.

I hope sharing examples of adaptations to systems we’ve worked on helps makes the case for getting more comfortable with change. One of the examples in the paper comes from my own experience of working with Sonpon Sieh, the head the Ebola response task force in Monrovia, Liberia. By January 2015, the nature of the Ebola outbreak had changed and the response needed to change too. There were fewer but more complicated cases, all located in the capital. The existing task force wasn’t structured to deal with this so Sieh, working with international partners, adapted the response. He decentralized it to four offices in different parts of Monrovia, a change that helped Liberia successfully manage the final cases of the disease.

Third, we can and should do more to build knowledge and tools on which delivery mechanisms work best when. For example, does it make more sense to try certain approaches depending on how politically powerful and hands-on a leader is? Or based on how decentralized the government is? Or how much capacity ministries have? I think those of us working on delivery can codify our learning more without falling into a best practices trap. The starting point for doing this should be more examples from different contexts, along the lines of those in Changing it up.

For AGI, there’s also room for improving how systematic we are about our process of learning and adapting. We have an internal toolkit which is a useful start. But we should push ourselves harder on things like explicitly working with our government colleagues to shape and test hypotheses and using more systematic “real-time experimental iterations”.

For governments and international partners working on delivery, the mantra of test and adapt may sound frustratingly close to “eat your broccoli”. But embracing this in practice, rather than going in with a set approach, is what it takes to create delivery mechanisms that generate real results for citizens.